I got my first synthesiser in my mid-teens. It was a Yamaha DX27, and the baby of the Yahama range at the time, but I was so excited to be given this as a Christmas present. I really wanted a Yamaha DX7 of course as most kids my age were into this kind of thing, but this was way too expensive. At the time, and this was in the mid-80s, FM synthesis was just replacing analogue as the new way of making sounds, but although there were a good amount of pop artists using this new technology, there were still a load of songs making use of older analogue synths. The new romantic and new wave movements were morphing into something else, the early 80s were still an inspiration to me for the kind of sounds I wanted to emulate, I mean, they still are, but for a kid my age growing up in the 80s, there was no such thing as retro, so we were all chasing the new at that time. So we had no choice but to move with the times. If I had known that this was the right time to buy up all the old analogue synths, I would probably be in a very different place now.

Having access to this new piece of equipment was a total joy though, I was in my element. I had owned a Yamaha organ prior to this, which was great fun but, I’d outgrown it, and who wants to be in a band and lug a great big Yamaha organ around? This synth seemed to have so many new sounds and instruments to play with but the real aspect of it that I wanted was that you could edit and store new sounds - kind of the point of a synthesiser.

The Yamaha DX27 uses FM Synthesis to create new sounds from an initialised sine wave. As this video shows it uses a stack of operators to create different patterns of modulation.

An operator is a simple oscillator in an FM (Frequency Modulation) synthesizer that produces a basic waveform, usually a sine wave. Operators can be modulated by other operators to create more complex waveforms and timbres. This is done using algorithms, which are essentially predetermined patterns of modulation between the operators.

For example, in a 2-operator FM synthesizer, the output of one operator (called the modulator) can be used to modulate the frequency of the other operator (called the carrier). This will create new harmonic content in the waveform produced by the carrier operator, and the resulting sound will be different depending on the specific algorithm being used.

There are many different algorithms that can be used in FM synthesis, ranging from simple ones with just a few modulations to very complex ones with many modulations between multiple operators. The choice of algorithm can have a big impact on the sound that is produced by the synthesiser.

I really got to learn quite a bit about synthesis during those early experiments, but what I really wanted to do was to do some multi-track recording. I got ready to start recording all these sounds that I had edited, but it soon dawned on my teenage mind that, there wasn’t a recording function. I couldn’t believe it, even the organ had a record function.

So I had to save up for a sequencer, which was a new concept for me. I saved up for one and bought one, but I can’t even remember now, which budget model it was I bought. Anyway, I plugged it in, Midi out from the keyboard, Midi in to the sequencer, made sure I was transmitting on midi channel 1, recorded a sound without too much difficulty, played it back, great, it works, but as soon as I switched the sound and tried to layer one on top, it dawned on me that there was another problem, this synth wasn’t able to record on more than one track at once. It wasn’t multi-timbral.

Again, I couldn’t believe my poor luck. Still I managed to have a lot of fun with that first synth and learned a lot about, amongst other things, Envelope Generators.

Which brings me to why I created this newsletter. Even though I have had periods in my life where I haven’t owned a synthesiser or even been making much electronic music, I have always had a connection to it and continued to be seeking out new sounds and ways to create something new.

The next step on this journey, once I left school, was when I got my first job. I worked in a large music store with a long tradition supporting the musicians of all kinds. I worked in the “hi-tech” department. Hi-tech was a buzz word back then for new technology. My job was to sell everything from guitars and their accessories, to woodwind instruments, brass instruments, but also synthesizers, amps and effects, and other pro-audio equipment. At the beginning of my job they said, probably the best thing anyone could have said to me at the time. “We don’t have time to teach you how to sell this stuff, so take home anything you want to learn about.”

This is when my interest in experimenting with audio, midi and synthesis took a more interesting turn. It meant I not only got an opportunity to really explore not just how to use all kinds of “hi-tech” equipment, but I got chance to record with the latest kit.

I got to experiment with a Yamaha CS80 analog synth, rack synths by Korg and Roland, and Yamaha, numerous effects processors and learn through experimentation how each effect worked, how signals flow and more importantly behave unexpectedly, when you connect different things together.

It was a real hub too of all kinds of visiting musicians from across the generations, and from every musical style you could imagine, pop, jazz, world, thrash-rock, punk, noise, anarcho-punk, blues, grunge, EDM, dub reggae, even some folk and sometimes from the original recording artists who came by the shop to try out a new instrument. So I got to hear lots of new music, lots of opinions about music, some informed, some not so informed. I really got to learn through my mistakes and how to take an experimental approach to music production.

I played in different bands and switched to playing guitar for a while. I learned the hard way that having the latest “does everything” effects box and the latest experimental guitar prototype with no headstock with tuning at the guitar bridge can be a recipe for disaster. So for a while, I turned my attention away from live playing in bands that wouldn’t advance my understanding of DIY music, to learning more about the craft of recording. First with 4 track tape, and then came the Atari ST.

The Atari ST was a home computer released by Atari Corporation in 1985. It was notable for its advanced graphics and sound capabilities, which made it popular with musicians and audio professionals.

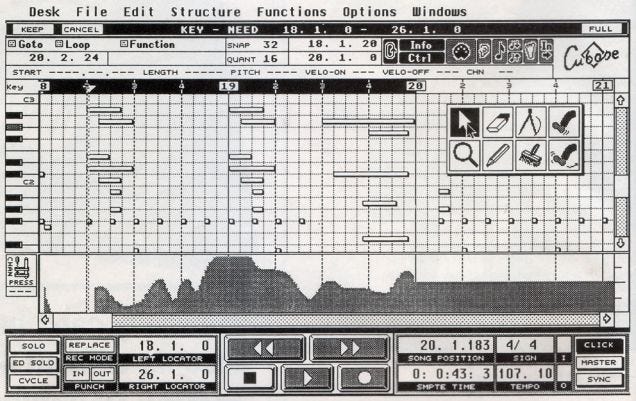

One of the key ways in which the Atari ST was a game changer, was because it had a MIDI interface. The Atari ST was one of the first computers to include MIDI which made it possible for me to use the Atari ST to record, edit, and play back music using Cubase. Steinberg Cubase was the go to multi-channel midi recording software for the DIY musician at the time. Now I was truly in the multitrack world, I was producing electronic music, not for an audience, but I was producing stuff for myself and a few people around me who would listen, at least.

The best thing about using the Atari ST was the internal clock, it was rock solid. This was because, the Atari ST used a hardware-based timer called the "Vertical Blank Interrupt," or VBI, which was responsible for generating regular timing pulses at a precise interval.

It really got me involved in learning more about midi

Source - http://www.muzines.co.uk/articles/steinberg-cubase/121

When I look at this now, it’s not that much different than a modern midi sequence view in Ableton or Logic etc. The basics of digital music production were already in place back in the late 1980s, but with one fundamental aspect missing . . audio.

Sampling

Sampling had been on my radar since the early 80s since I saw musicians like Herbie Hancock and Nick Rhodes of Duran Duran discuss how they were using a Fairlight CMI.

The Fairlight CMI was a powerful instrument that allowed musicians to create, sample, and manipulate sounds in ways that were not possible with analog synthesizers of the time. It featured a built-in keyboard, as well as a number of external input and output ports for connecting other instruments and audio equipment.

One of its most notable feature was the ability to sample sounds and play them back at different pitches, which was a groundbreaking feature at the time, allowing it to take the sounds of real instruments, record them and then use them in the digital domain.

The Fairlight was used by a number of famous musicians and bands in the 1980s, including Peter Gabriel, Kate Bush, and Jean-Michel Jarre, and played a significant role in popularizing digital music production.

Additionally, the software of the machine, Page R, was also a pioneer in digital audio workstations (DAWs) that would later the standard for most computer-based music production studios.

But seeing as my entrance into the world of electronic music was a Yahama DX27, the chances of me owning a Fairlight back then was next to none.

From the other end however, sampling was making waves in the early DIY music production circles via the rival machine of the Atari ST at the time in the Commodore Amiga.

I had heard samples twice prior to this once when my ZX Spectrum computer rather impressively for the time shouted out “Ghostbusters” and the second time was when a computer-savvy friend of mine showed me flesh 4 fantasy demo on the Commodore 64.

It doesn’t seem that impressive to our modern ears, but the point is, that when I first heard this and the previous example, I had not heard an actual recorded audio sample coming out of a computer before. For 1983, this was groundbreaking and I could project what the future might be for music production.

I didn’t truly get into sampling until I got hold of a Akai S1000 around late 89. My first sampler was the keyboard version, which I was told used to belong to Dave Greenfield.

It was an impressive machine, great to play but not very portable. It was a great introduction to learning how to sample instruments and loops and hook those loops and samples up to be triggered by cubase.

I made a lot of music in the late 80s and early 90s, most of it pretty terrible and most of it I haven’t got any evidence of, but I was learning a lot about music production. I experimented with lots of different styles and through this period up to the mid 90s partly through continuing to work in an around music production on and off in the hi tech music shop, but also recording with various bands I was in mainly as a guitarist, I was introduced to lots of different techniques and I soaked it up as much as I could.

Although I was still recording and playing in bands in the mid 90s to the early 2000s, I took a bit of a departure from electronic music and music production in general. I enrolled on a degree course in Creative Writing, I thought I’d try something new to see if I could change my job and direction whilst still developing my music production skills on the side. By this time I was working on an early Pentium PC and PC and MAC music production within a DAW was become the standard.

I flitted between early versions of Cubase, Cakewalk, Logic and Reason and spent a lot of time trying to get acquainted with the these programs which were a steep learning curve to begin with. I finally settled on Logic starting in version 4.0

https://www.soundonsound.com/reviews/emagic-logic-4

As you can see, the interface is starting to resemble a modern DAW. I spent a few years more recording with Logic and learning all I could about it, using it for general music production, sampling, triggering rack synths, and playing around with, and often breaking, the Environment, Logic’s complex backend view of midi connections and system exclusive messages.

My perseverance with this, although I wasn’t aware of it at the time, was about to pay off as it enabled me finally to change from working in retail to working in education.

I got a job as an assistant lecturer in music technology at a local college. From here, I was able to embed my learning around Logic, Pro Tools, Max-MSP, and more experimental applications with audio and sound design.

In my current role as a lecturer in games, animation and VFX, I have expanded my approach to incorporate audio and sound design processes for games, including audio and synthesis within the framework of game engines like Unity and Unreal further fallen down the rabbit hole of developing audio prototypes using Arduinos and the Raspberry Pi. I think I am now finally at the point where I can fuse everything together in more experimental ways.

I recently mixed and mastered my first full album for the Horses of the Gods. This was an album I produced with the help of my fellow music producer Matty Bane. It has very little to do with electronic music, but our attention is now focused on how we can build ambient and experimental audio and synthesis into our music.

So this leads me to the point I am at right now. I don’t know entirely or in fact at all in which direction I am going with both my music and my understanding of everything to do with music production but I am very happy to be in this place.

The possibilities of developing my understanding of sound design, composition, DIY experimental music prototypes and audio programming techniques, is all too exciting to ignore.

So I am hoping that this substack newsletter will become a kind of record of my experiments from this point forward in which I aim to as entertainingly as I can, push the envelope generator.